Deconstructing a problematic housing program

Data collected by Mount Holyoke students has shown a major policy flaw in a program originally meant to fight housing blight.

When Nicole Villacrés ’18 was trying to figure out a topic for their thesis, they had one main goal in mind: “I wanted it to be something that was useful. I wanted it to be actionable. I didn’t just want it to be something I was going to write that lived and died with me,” Villacrés said.

Five years later, their thesis has proved to be as actionable and as useful as they had hoped.

In late March, work done by Villacrés and other members of Vanessa Rosa’s 2017 class Latinxs and Housing: Mi Casa Is Not Su Casa helped housing advocates in Springfield push back against a predatory program called “receivership.” Having data collected by a neutral third party — especially an academic one — was key to getting city officials to recognize the housing policy as problematic, said Rose Webster-Smith, the executive director for Springfield No One Leaves. “With this research, we were able to say, here’s the data; it speaks for itself. Look it over. And when you’re done looking at it, give us a call,” she added.

This story starts back in 2016, when Vanessa Rosa, Class of 1929 Dr. Virginia Apgar Assistant Professor of Latina/o Studies, connected with Springfield No One Leaves. Founded after the 2008 housing crash, Springfield No One Leaves is a grassroots organization focused on keeping community members in their homes. Rosa connected with Webster-Smith to see if there was a way to partner as part of Mount Holyoke’s Community-Based Learning program. Webster-Smith immediately put Rosa’s students to work as canvassers. They would meet with residents facing eviction and help them navigate next steps.

In 2016, Nicole Villacrés was one of those canvassers. The work spoke to them, and when the semester ended, Villacrés kept showing up to volunteer. The following year, they became a Community-Based Learning Fellow, helping out Springfield No One Leaves for 10 hours each week. In that work, Villacrés started to notice something Webster-Smith had been keeping a close eye on: Community members were coming to the organization asking for help when their homes fell into the city’s receivership program.

Receivership is supposed to be a tool cities can use to seize empty homes that have become health and safety hazards. The town assigns an abandoned home to a receiver — usually a private partner — who fixes it up. The partner places a lien on the house for the value of the repairs. If the homeowner cannot pay off the lien, the city can then foreclose or auction off the property. In 2015, Springfield’s mayor boasted about the success of Springfield’s receivership program and how it had restored hundreds of blighted properties into livable units. A housing court judge even called the program “the gold standard.” But Rose Webster-Smith could see that this glittering program was anything but solid gold.

While receivership can be a useful tool for dealing with abandoned homes, in Springfield, code-violation complaints were sending occupied homes into the program, said Webster-Smith. Private companies would then begin renovations — often without the homeowner’s consent — and stick the homeowner with the bill. Meanwhile, real estate investors saw the receivership program as a way to snap up properties at a low cost.

In 2017, Villacrés told Webster-Smith that they were looking for a thesis topic. Webster-Smith suggested an in-depth look at how, exactly, the receivership program worked and who were its winners and losers.

“What Rose [Webster-Smith] asked us to do was very complicated. I knew we could do it, but I knew I would need support,” said Rosa about the effort. To aid Villacrés, Rosa brought in that year’s Latinxs and Housing class. Villacrés showed the class how to wade through records at the registry of deeds and track down the owners of homes that had gone through the receivership program.

Over the course of a semester, 15 students in Rosa’s class spent between 200–300 hours researching deed information for every single home that had entered Springfield’s receivership program. They noted why the home fell into receivership and whether the owners had abandoned it or were still living in the dwelling. Then they tracked whether the original owner retained the home. Then they double-checked everything. “We knew we had to get this right,” said Rosa.

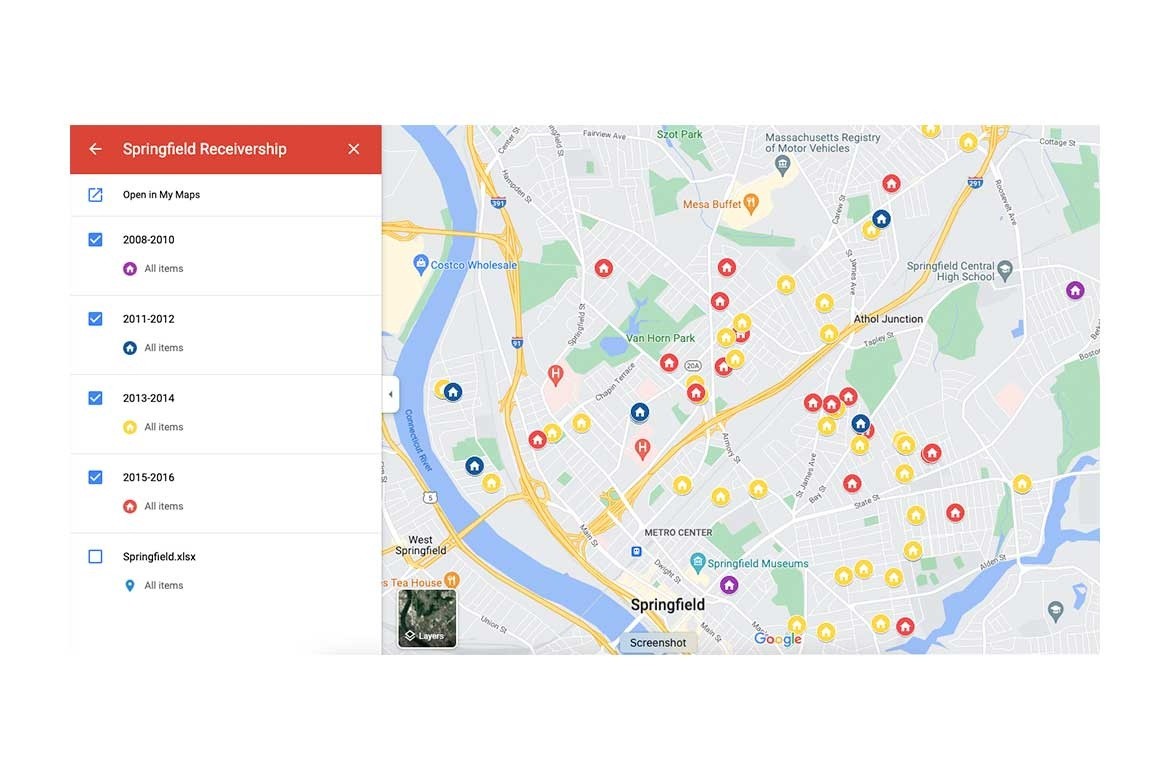

Once the class had constructed a monster database, James Burke, a research and instructional librarian at Mount Holyoke, helped the students plot the homes on a map. When finished, the map made it clear to Villacrés and students in the class that homes in receivership were not spread equitably across the city — even though every area of the city had abandoned units. Black and other diverse neighborhoods had seen more houses go into receivership over the years, they said.

In the end, calculations done by the class found that as many as 51% of homeowners lost their homes through the receivership process. “People think this is happening with empty or abandoned housing, but here we are with homeowners who want to stay in their properties,” said Villacrés. “And they were taking away property that could have been creating generational wealth for that family.”

When Villacrés finished their thesis, they handed it to Springfield No One Leaves. “I said, ‘This is yours to move forward with.’”

Webster-Smith didn’t waste a single minute putting the data to work. She sent the findings off to the city council. “Most of the city counselors that we approached didn't even realize the receivership program had moved beyond vacant homes,” she said. The mayor, too, was dismayed to learn that the city’s “gold standard” program was actually responsible for pushing families out of the homes they had paid mortgages on for years.

In late March 2022, the city council approved an ordinance that would allow the city to set up a housing trust. Homeowners at risk of falling into the receivership program will be able to use this trust to fund needed repairs. The trust will offer grants, not loans, so there’s no risk of accruing a debt the homeowner cannot pay off, said Webster-Smith.

As the city council debated the housing trust, Villacrés, who now lives in Maine and works as a cabinet maker, kept in close contact with Rosa and Webster-Smith. “It’s been very exciting,” they said about watching their thesis translate into actual policy — just like they’d always wanted.

However, it doesn’t surprise Rosa that her students are having a big effect on the world around them. “The core of Latina/o studies is thinking about our relationship to the communities around us and addressing injustices and contributing to transformation.”

Which is exactly what one small community-based learning initiative turned into: an effort to engage with the community and address the injustices within it.