Digging deeper into climate change

Mount Holyoke senior Bridget Hall ’24 spent her summer on a “pretty special” glacier in Canada, doing research into climate change for an internship that confirmed her interest in glaciology.

While much of the world is experiencing heat waves like no other, Bridget Hall ’24 spent her summer internship camping on a glacier between two mountains in Canada. The researcher leading the project believes such work can deepen (no pun intended) scientists’ understanding of climate change.

Hall spent a month as part of an ice core drilling project between Mount Waddington and Combatant Mountain in British Columbia.

A double major in geology and environmental studies, Hall engaged in what she describes as a life-changing internship that ultimately decided what she intends to be her life’s work: geology that’s specifically focused on glaciology and paleoclimatology.

If that sounds abstract, well, it’s actually so concrete that a drill is a key tool for research.

Hall, 21, a Mount Holyoke senior from Arlington, Massachusetts, spent her first-ever internship working on the team led by University of Minnesota glaciologist and earth scientist Dr. Peter Neff, who happens to be married to Mount Holyoke alum, also a climate scientist, Dr. Heidi Roop ’07.

This summer Neff led a 12-person team on a National Science Foundation–funded project to collect an ice core from a glacier to produce a 500-year record of hydroclimate in southwestern Canada. He believes glacial ice can further scientists’ understanding of climate change.

Hall’s internship actually started two weeks before the team set foot on the glacier. In June she flew to Minnesota to work with Neff, assembling supplies and packing the van that would ferry equipment, research supplies, camping gear and food about 1,500 miles to British Columbia, Canada.

They spent three days driving that packed van to Seattle, where they met up with other members of the team, including one of Neff’s collaborators, University of Washington Professor Eric Steig, and doctoral students working on the project. In Seattle they spent a couple of days in meetings with the team, planning logistics and working out other details before setting off on the 12-hour drive to base camp.

From base camp, the team took a 30-minute helicopter ride to the site of the Scimitar and Tiedemann glaciers, where they would live and work for the next 22 days, drilling into the glacier and describing and preparing the samples they pulled up for shipment.

For anyone wondering what riding in a helicopter to a remote location at the base of a mountain at the site of a glacier is like, Hall cheerfully reported that the ride “was a little nerve-racking.”

As for camping on top of a glacier, Hall, who has years of camping experience (though no winter camping experience), found that part not very difficult.

“It wasn’t actually all that cold,” she said. She explained that the team worked at what’s known as a temperate glacier, which is precisely why the team was there.

“There’s not a lot of ice core research done on temperate glaciers,” she explained. At the Mount Waddington glacier, though, the snow accumulates so thickly that even with the melting that occurs, there remains enough snow to protect the glacier.

“So that’s pretty special,” she said.

Setting up camp smack on top of the glacier included erecting a large communal tent with a kitchen set up, digging special holes in the snow for bathroom needs and setting up individual sleeping tents.

Then they got to the real work, which involved three team members working with the thermal drill that melted its way deep into the glacier ice, slightly melting it as it drilled down, and three core processors.

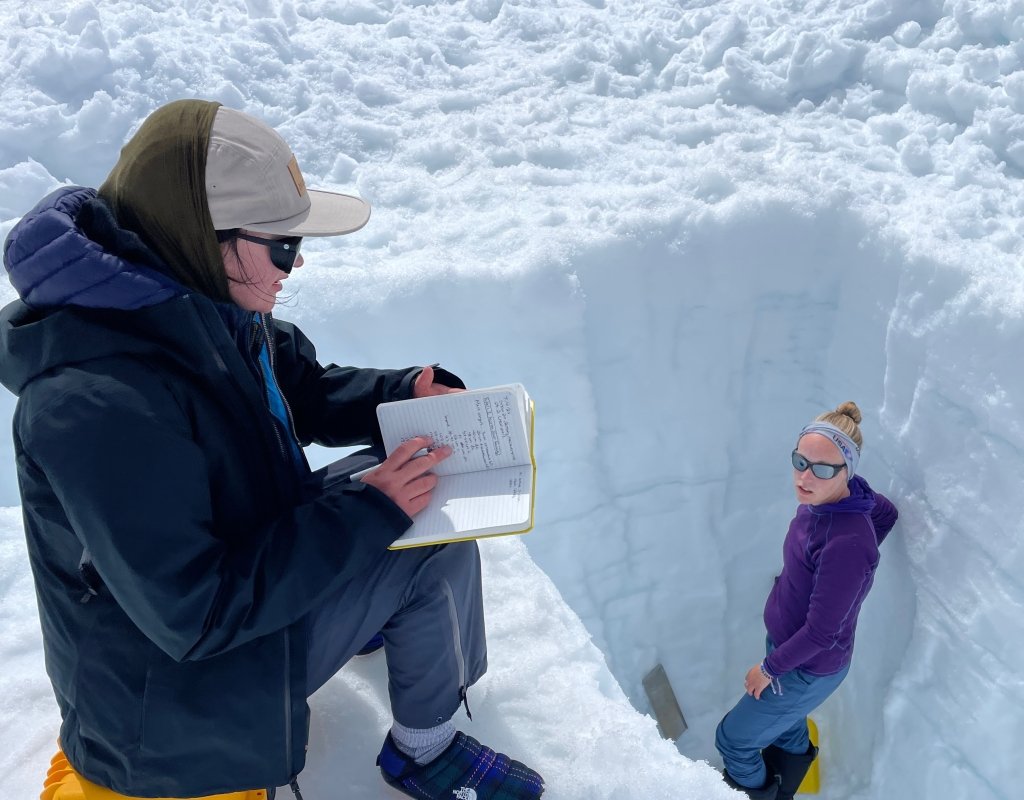

Hall was one of the core processors, which meant she took two-meter long ice cores, cut them into one-meter sections and described them to document and record key elements such as sediment and evidence of melting and bubble zones. These are all clues into the past life of this glacier.

She then placed the sections of glacial ice in plastic bags and labeled them so researchers could later identify key details (such as which end was up) when they did more testing. Core processors then buried the bagged specimens in a large pit of snow they’d dug to keep them frozen until the helicopters came (every few days) to take the harvested cores back to base camp in sling loads (sturdy nets handing off the helicopter), where they were placed in a metal storage container.

The team’s goals were to obtain core samples big enough to undergo further analyses back in the research lab.

The purpose of those tests, Hall explained, is to understand “spatial dynamics of the past climate.” Yes, Hall already speaks in the particular language of glaciologists, but she can translate for the layperson, which she did when asked: Scientists are trying to understand how this specific area underwent climate change.

By looking at lead content, sediment and black carbon sediment, researchers gain a deeper understanding of the evolution of climate change and the role of greenhouse gas emissions.

“It’s definitely not about how we can stop climate change. It’s more just research on how it’s changing and how it’s changing in that local area,” Hall said.

Understandably, spending a month on a research team at a glacier involved hardships. For Hall, one was that she was the only undergraduate on a team of people who had significantly more experience and education than she had. “That was pretty intimidating,” she said. She found the team welcoming and helpful, and she says that in addition to learning a lot, she made friends in the process.

In terms of keeping up with team members with more experience and education, she needn’t have worried.

“Bridget was a fantastic research assistant, one of the best that I’ve ever worked with,” said Neff in a telephone interview July 24, the day he returned home after the final leg of his trip.

“She contributed to our research in a big way,” he said. And because her travel was partly funded by the Center for Oldest Ice Exploration (COLDEX), she will have to miss some of her first week of school in September in order to present her work at the group’s annual meeting.

And while all the locals informed team members that they were “extremely lucky” with the weather during their time at the site, there were a few days of weather that were, in Hall’s words, “a little scary and a little sketchy” — enough to bring a temporary halt to their drilling.

For those periods, the team largely stayed in their tents, listening for hours to the incessant snapping of the tent flaps and loud, heavy winds outside. And while she was never bored, there was a feeling of “constant waiting,” such as when the core processors had to wait for the drillers to bring them samples to describe.

Sometimes the team came together in the big tent, where Hall says they had long talks. She also crocheted a sweater.

“The bathroom situation was definitely something to adjust to,” she said. The team dug holes to pee in and had to make use of a “wag bag” for other needs, which they then stored for later removal from the site.

“You had to be flexible and accept it,” she said.

Hall said she hoped the internship would clarify for her what she wanted to do with her life. On that score, and many others, it was a resounding success. She intends to spend the rest of her summer figuring out to which geology Ph.D. programs she wants to apply.

“Getting up on to Waddington, up onto the col, solidified that I’m absolutely interested in research,” she said. “I am absolutely interested in ice cores and glaciers.”

Geology Professor Alan Werner, Hall’s academic advisor, worked to help Bridget secure the internship because he felt the experience would be essential to her education. She had taken many classes with Werner and had worked as his TA. “She’s one of the best,” he said, “one of our top students.”

To help her find a suitably challenging internship, Werner reached out to his networks of colleagues and former students, ultimately connecting her to Roop, another one of his top students, he said. Roop is an assistant professor and director of the University of Minnesota Climate Adaptation Partnership. In addition to having a background in paleoclimate, Roop combines cutting-edge climate science and effective science communication to increase the use and integration of climate change information in decision making. She published her first book, “The Climate Action Handbook,” earlier this year.

Roop happily connected Hall to her husband, who was heading to the glacier for summer research.

Werner says reaching out to Mount Holyoke graduates is often fruitful like that. “Don’t underestimate,” he said, “the power of the alum network.”